Courtesy Iki.lk December 31, 2023

Ravinatha Aryasinha*

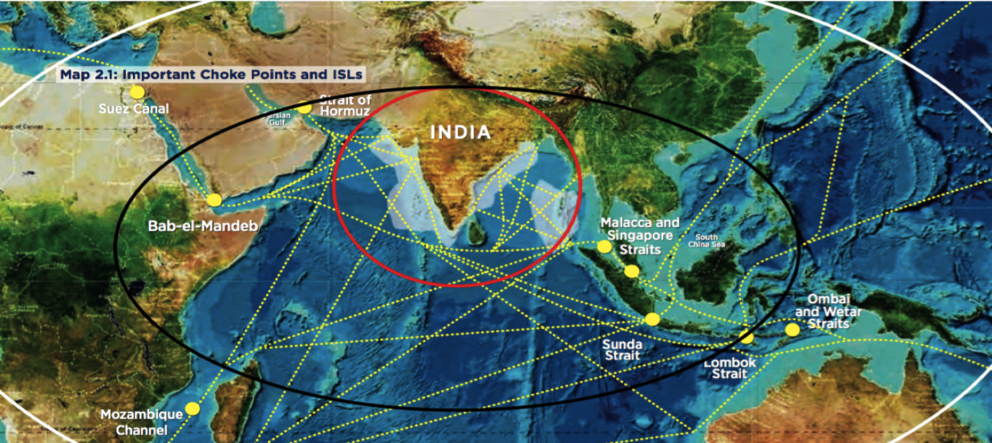

Abstract: The paper discusses the impact of major power rivalry in the Indian Ocean Region and assesses the foreign policy challenges for Sri Lanka. Drawing on a presentation made at the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies (RCSS) Regional Conference on ‘Ocean Security: South Asia and the Indian Ocean’ – 16 October 2023, it reviews the associated dynamics, identifies the flashpoints, and suggests modalities that could help Sri Lanka overcome the predicament of becoming a battleground for confrontation between the major powers.

- Introduction

The past decade has seen the emergence of growing competition in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), driven by the conflicting strategic visions of the major powers. This power rivalry has been dominated by China’s 2013 Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the U.S.’s 2017 ‘Indo-Pacific’ strategy (IPS). There have also been other conceptualizations posited by: India through its ‘Neighbourhood First’, ‘Look East’, and ‘Security and Growth for All in the Region’ (SAGAR) policies; Japan’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’; ASEAN’s ‘Outlook on the Indo-Pacific’; Australia’s ‘Foreign Policy White Paper’; France’s growing involvement in the Indo-Pacific and projection of a ‘Third Way’; and, more recently, the extension of the European Union’s ‘Global Gateway’ programme which has been interpreted as a western-led response to the BRI to also cover South Asian countries.

Notwithstanding these multiple visions on the Indo-Pacific, the major power competition in the IOR continues to revolve around the U.S, China, and India. Given its strategic location in the Indian Ocean and longstanding relations with all the 3 countries, Sri Lanka has been at the centre of these complexities. The narrative in this regard appears to have been dominated by China’s competitors, who in their attempt to counter Chinese influence in the region, have portrayed the Hambantota Port project as the “top candidate for a future base of China” (Wooley and Zhang, 2023); posited a “debt trap” narrative around Chinese lending to Sri Lanka (Tharoor, 2022), and continue to call on Sri Lanka to take a stronger position against “visitations by Chinese vessels”(Laskar, 2023, 2023; Indian Express, 2023).

- Effects of Major Power Rivalry in the IOR on South Asian States

In the IOR, all Smaller South Asian states (SSAs) – Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and the Maldives, face challenges similar to that faced by Sri Lanka concerning major power influence. While excluding India and Bhutan, six out of the eight South Asian States have joined China’s BRI, and with the exclusion of Bhutan, and seven out of eight are also members of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), none have joined the US-led IPS. However, India stands out as the only South Asian state that is a member of the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) which also includes Australia and Japan, as well as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Assessing the extent of integration of SSAs in the IPS, Samaranayake (2023a) notes that “the implication of the IPS is that the smaller countries in the region are to be led by India, inadvertently suggesting that Washington is outsourcing policy to the largest, most populous, and economically and militarily powerful country in South Asia”. This concern has also been voiced in discussing Sri Lanka – US relations (Martyn, 2023).

Even as the SSAs position themselves to grapple with the prevailing global order, relationship dynamics and tensions between and among major players in the IOR – the US, China, and India, have considerably influenced not only the foreign policies but also the domestic policies in SSAs. This was evident during the recently concluded Presidential elections in the Maldives (Macan-Markar, 2023) and has also intensified in the run-up to the forthcoming Parliamentary elections in Bangladesh (Hasan, 2023). As with these two countries, it is also increasingly affecting the dynamics in Bhutan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka – having a bearing on economic development (Banerjee, 2023), sought to influence the governmental decision-making processes (Reuters, 2021; The Straits Times, 2020; Pradhan, 2023), and has effectively also polarised the public discourse (Fernando, 2023).

So far, Bangladesh is the only SSA state to outline a formal composite response to the challenges associated with this power competition in the region, through the ‘Indo-Pacific Outlook of Bangladesh’ (IPOB). Introduced in April 2023, it advocates for a free, open, peaceful, secure, and inclusive Indo-Pacific (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh, 2023). It reflects an acknowledgement of the global and regional geo-political environment which is not of its making, seeks to prevent being subsumed or being appropriated, and projects a determination to assert the country’s independent identity.

As for Sri Lanka, President Ranil Wickremesinghe has referred to the multiple visions on the IOR as “constructs” (PMD, 2023b), and differentiating the Pacific Ocean from the Indian Ocean, has expressed concern that the problems of the former were being brought into the latter. He has also asserted that the island nations in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific have distinct priorities, unrelated to the QUAD or China’s objectives (PMD, 2023a).

- Analysis of Sri Lanka’s Strategic Posture & Behaviour

In dealing with the aforementioned challenges and seeking conceptual clarity as to the ‘strategic posture’ adopted by Sri Lanka in serving the country’s ‘national interest’, historically, the most frequently referred to has been the concept of ‘non-alignment’. However, in recent times, the relevance of non-alignment has increasingly been questioned in the political context of a multi-polar world, and the sustainability of Sri Lanka’s non-aligned foreign policy critiqued as weakening the country’s position in trade negotiations (Weerakoon, 2023). There has however been very little Sri Lankan scholarly attention paid towards a conceptual re-appraisal of non-alignment in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy – whether it continues to remain a viable foreign policy posture for Sri Lanka, and if not, what has or should replace it.

Nevertheless, there have been other varying readings by experts of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy behaviour which could be characterised as – ‘bandwagoning’ (Gunarathne, 2021: Smith, 2019; Jayasekera, 2022), ‘balancing’ (Gunasekera, 2015; Senaratne, 2023b:20), and ‘hedging’ (Kandaudahewa, 2023:122). Sri Lanka’s hedging behaviour has also been caricatured by analysts in the immediate aftermath of the extension of the lease on the Hambantota Port in 2017 using the term ‘strategic promiscuity’, albeit with different emphasis (Hewage,2017; Coomaraswamy, 2017), and more recently as ‘enforced agnosticism’ (Hewage, 2023). The conclusion drawn by Manatunga (2023) who applies hedging to a case study of Bangladesh and observes that for SSAs hedging appears to have moved beyond being a mere ‘survival mechanism’ as seen in the Southeast Asian context, to have helped states to leverage power rivalries in order to maximize national gains (p. 31), also seems eminently applicable in Sri Lanka’s case.

In contrast, analysing the 2014 Chinese submarine visits to the Port of Colombo and the controversies that followed, Samaranayake (2023b) has argued that “the country was not balancing against India, bandwagoning with China, or even hedging” and that Sri Lanka’s foreign policy decisions were “driven primarily by domestic-level factors”. In a recent assessment of Sri Lanka’s posture with respect to the major power rivalry in the IOR, she has argued that “when a smaller state faces pressure at the system level, the choices it makes are not necessarily between bandwagoning, balancing or hedging, but rather the pursuit of domestic-level interests and preferences; with “bandwagoning as a last resort” (p. 62).

However, ‘neutrality’ – a term mainly used by the Gotabhaya Rajapaksa administration (November 2019 – July 2022), has been that most mentioned of by analysts to refer to Sri Lanka’s foreign policy posture in recent years (Aryasinha, 2023a). Ladduwahetty (2023) advocates that “The policy of ‘neutrality’ is the best defence Sri Lanka has to deter global powers from attempting to gain control of Sri Lanka because of its strategic location on grounds of internationally recognized norms of conduct applicable to a Neutral State”. Lottaz andJayathilake (2021) have also observed that “despite good reasons to doubt the sincerity of the approach”, “It (neutrality) also gives the government the possibility to fence off encroachments from all sides, including China. In particular, worries about territorial sovereignty over ports make a neutrality policy a viable and sensible option” (p. 3). Palihakkara (2023a) in a critique of recent foreign policy practices in Sri Lanka calls for a more nuanced evaluation, emphasizing that “alliance neutrality, not alliance partnership, is the sensible bet for the likes of Sri Lanka, to maximise and possibly leverage its strategic location value”. Commenting on the tendency by successive Sri Lanka governments to engage in transactions in order to appease India, China and the US, he has opined that “rather than demarcating ‘zones’ for different investor States thus ‘parcelling out’ our sovereign assets including land to contending powers (e.g. quasi-vasal state projects in Trinco, Hambantota etc.), the whole of Sri Lanka can become a venue supporting multinational investment and multilateral cooperation for growth and development”.

However, the application of the concept of ‘neutrality’ to the Sri Lankan context is problematic. The International Committee of the Red Cross (2002) describes neutrality as the formal position taken by a state which is not participating in an armed conflict, and also intends to remain uninvolved. This status entails specific rights and duties where, on the one hand, the neutral State has the right to stand apart from and not be adversely affected by the conflict, while, on the other hand, it has a duty of non-participation and impartiality (p.6). Though widely used, what precisely ‘neutrality’ entails in situations where an actual armed conflict is not taking place, and also not imminent, remains unclear. Clarifying the precise contours of neutrality in these situations is crucial for establishing a framework that fosters stability, peace, and effective diplomatic engagement on the global stage.

Beyond the absence of direct military involvement, while neutrality may imply a commitment to impartiality in the face of geopolitical tensions, it necessitates a state’s ability to consciously navigate a delicate diplomatic course, avoiding alliances or actions that could compromise its perceived impartial stance. Neutrality extends to economic engagements as well, requiring a careful balancing act to ensure that trade and partnerships do not align with the interests of conflicting parties. Additionally, while maintaining neutrality involves active diplomacy to contribute to conflict prevention and resolution through peaceful means, there is also the expectation that it must be acknowledged and respected, by the concerned competing powers.

- Assessment of the dynamics of Sri Lanka’s relations with India, China and the US

A careful assessment of the current ‘balance sheet’ of Sri Lanka’s core triangle of foreign relations with India, China and the US makes clear that the relationships with all three countries are important for different reasons and in that sense are indispensable in their own right (Aryasinha, 2023 c). Sri Lanka cannot afford to forego it’s major export market in the US and Europe, as much as it is conscious that its future prosperity can be enhanced by hitching on to the Indian growth cycle, but at the same time it has to depend on China (and also Russia) in the face of the multilateral affronts it faces in the realm of human rights. This is likely to remain so in the foreseeable future.

However, other than with some exceptions (particularly, India’s economic assistance during the recent economic crisis and support with the IMF; China’s military assistance to fight the LTTE and diplomatic support in defending Sri Lanka’s human rights record; and US intelligence support in fighting the LTTE and provision of COVID vaccines), a closer reading of approximate events in relation to much of the project assistance offered by these countries to Sri Lanka indicates, that they were largely for unsolicited projects, few which made a tangible impact to Sri Lankas’s GDP, and have been considerably transactional – both in terms of advancing their respective national interests, and also in preventing the other states from gaining a strategic advantage in Sri Lanka.

On Sri Lanka’s part, notwithstanding official pronouncements of being nonaligned and/or neutral, successive political administrations, particularly post-2009, have engaged in what would appear to be ‘pendulum swings’ in foreign policy – alternately hedged their bets with each or some of the three contending major powers. This has resulted in situations where the country has been entrapped in complex situations caused by untenable commitments extended to different powers at different times, to the exclusion of the others. Such an approach has not only proved unhelpful but has also generated a vicious cycle of mistrust and a loss of credibility. Additionally, there has been the tendency for Sri Lankan decision makers, economic actors, civil society, and even the writings of the communicational elite, to be also vulnerable to the polarisation efforts by all the three major powers and their proxies.

It is also noted that in the first decade of the 21st century, despite the growing tensions between China and the US/India, none of the major powers in the region had demanded ‘exclusivity’ or for Sri Lanka to be in their respective ‘spheres of influence’. In fact, a former High Commissioner of India to Sri Lanka, former Foreign Secretary, and India’s National Security Advisor until mid-2014 Shivshankar Menon (2016), has observed that “At no stage was exclusivity sought or promised [from Sri Lanka]. Realistically speaking, it would be unreasonable to expect exclusivity” (p.150). He recounts with reference to the ‘Troika arrangement’ that helped manage Indo-Sri Lanka relations since 2008 at the height of the terrorist conflict, that Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa and President Mahinda Rajapaksa gave the Indian side assurances that “India’s security interests would be respected and that there would be no surprises in Sri Lanka’s relations with China”, adding that “These assurances were respected in practice by the Sri Lankans until May 2014” (p.139). However, in the face of increased power rivalry in the Indian Ocean, this atmosphere appears to have changed considerably over the past decade, and exclusivity has increasingly been demanded from Sri Lanka by all the major powers with respect to their bilateral relations with Sri Lanka (First Post, 2023; Chaudhury, 2023).

It is noteworthy that this escalation of the situation, has been notwithstanding, and in fact contrary to, the more considered recommendations made in strategic assessments by countries such as the US, and also unresponsive to Sri Lanka’s own efforts at times to re-balance. Externally, despite the pressure imposed by the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora (Shain & Aryasinha, 2006), most prominently the December 2009 bipartisan Lugar-Kerry Report of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (2009) had counselled that the US strike a balance in its relations with Sri Lanka particularly conscious of the strategic importance of the island, and that “The United States cannot afford to lose Sri Lanka” (p.3). Internally, despite in 2015 the National Unity Administration’s (NUA) early efforts at re-balancing away from China and acceding to many of the demands of the US in particular and Western powers in general – both on strategic and human rights concerns, data reveals that in the period 2015-2019 there was no notable increase in trade, FDIs or financial development assistance to Sri Lanka from the US and the West (Wignaraja, 2022: 86). Most recently, in September 2023, participating in the ‘Ocean Nations: The 3rd Annual Indo-Pacific Islands Dialogue’, President Ranil Wickremesinghe was to also assert that, Sri Lanka’s government does not align itself with either India or China, and firmly stands for Sri Lanka’s interests above all else, adding “I’m not neutral, I’m pro-Sri Lankan” (PMD, 2023a).

Notwithstanding the above efforts, the present reality facing Sri Lanka is that even on occasions that Sri Lanka has adopted a strictly non-aligned/neutral approach, concerned countries and alliances have brought pressure on Sri Lanka to operate in a ‘zero-sum’ environment – “being a situation (such as a game or relationship) in which a gain for one side entails a corresponding loss for the other side”. Drawn from ‘Game Theory’, a zero-sum game is one, such as chess or checkers, where each player has a clear purpose that is completely opposed to that of the opponent. (Merriam Webster, n.d). It is argued that this is effectively the situation Sri Lanka faces at present. How Sri Lanka can resist and overcome this increasingly ‘zero-sum’ push will be the crucial test for its foreign policy in the foreseeable future.

- Approximating a Sri Lankan response in an increasingly zero-sum environment

Hence Sri Lanka is challenged to carve out a foreign policy, which while avoiding being drawn into the crossfire between the major powers operating in the region, allows space for the country to remain relevant, to be secure, and to prosper. In managing this predicament, Sri Lanka can draw inspiration from the fact that, in the past, Sri Lanka’s interests were best served, and Sri Lanka’s greatest contributions to the international community were made, when it adopted centrist positions, rather than positioning itself in a manner that either allowed it to be lumped in polarized/factionalized camps, or when Sri Lanka remained isolated.

The crafting of foreign policy should also be done in a manner that is sensitive not only to the concerns of India, China and the US, but also with a view to securing leverage with Sri Lanka’s other key longstanding and emerging interlocutors – particularly the ‘Middle Powers’, who in recent times have been somewhat neglected due to Sri Lanka’s pre-occupation with the major powers. This should include prominent economic partners such as Australia, Japan, the UK, and the EU; political partners such as Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, all of Sri Lanka’s South Asian neighbours; as well as other member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC), and the African Union (AU) – all with stakes in the IOR, and relevant to Sri Lanka’s wider challenges in the multilateral sphere.

Ironically, the economic crisis of 2022 could in retrospect be considered to have to some extent allowed Sri Lanka sufficient wriggling space to avoid being forced to choose between different powers in the conduct of its foreign policy, and to enable it to gravitate to the middle. As a result, despite strong bilateral differences that persist among the major powers and following complicated negotiations over 20 months across a multitude of platforms, Sri Lanka has been successful in securing the international collaboration necessary for the release of the first two tranches of a total 2.9 billion USD under the IMF Extended Fund Facility (EFF). Participating in the vote of the Foreign Ministry during the Budget Debate on 7 December 2023, Foreign Minister Ali Sabry was to assert that “staying clear of any camp has paid dividends”, and that “a sound foreign policy helped fast track debt restructuring” (Mudugamuwa, 2023). The IMF has acknowledged that “Sri Lanka’s agreements-in-principle with the Official Creditors Committee and Export-Import Bank of China on debt treatments are consistent with the EFF targets” and “are an important milestone putting Sri Lanka’s debt on the path towards sustainability” (Financial Times, 2023). Sri Lanka now requires striking a deal with its commercial creditors and bondholders, as the IMF has asked Sri Lanka to secure debt treatment deals with all creditors ahead of the second review in June 2024 (Daily Mirror, 2023). It is important that the present momentum must be availed of as a catalyst in re-positioning Sri Lanka, and in also addressing some of the other contentious issue areas on Sri Lanka’s foreign policy agenda. It is important that this be done resisting the external pressures being exerted from all sides, and also evolving a national consensus on a sustainable strategic posture that could be adopted by Sri Lanka.

While Sri Lanka’s main focus in the immediate term no doubt will be to overcome the current economic crisis and its multifaceted ramifications, in parallel, Sri Lanka’s diplomacy also has the challenge to restore the country’s image as a serious multilateral player, in order to regain its lost leverage in the international sphere. Sri Lanka must engage across the full canvas of international issues – both pursuing its immediate national interest, as well as engaging on issues which have broader global resonance and bearing. Rather than allowing itself to be pre-occupied with largely a reactive foreign policy – on issues such as human rights and the major power rivalry in the Indian Ocean region, Sri Lanka diplomacy is increasingly being challenged to be pro-active. Sri Lanka’s recent initiatives on environment and climate change, as well as on maritime issues are useful step in this direction. Sri Lanka could also project its historical global role played in areas such as disarmament, peacekeeping, world economic order, counterterrorism, as well as emerging priorities such as South-South Cooperation, migration, climate resilience, efforts to mitigate maritime crime, and the debate concerning Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS), on which the country has developed considerable expertise in recent times.

In the security realm, Sri Lanka must not leave cause for concern with respect to India’s legitimate security interests that could emanate from Sri Lanka. In this context, the current demands for exclusivity could be averted through greater transparency in dealings, so that when concerns arise, as happened during the final phase of the terrorist conflict with the LTTE, objective verifiable processes are in place to ascertain the veracity of the same and to trouble-shoot where necessary. In this context, Palihakkara (2023b) has observed that “the overarching challenge that is faced by Sri Lanka in its foreign relations, is demonstrating that it is after tangible economic benefits and not geopolitical mischief in the Indian Ocean”.

Sri Lanka must also retain the space to engage in transactions with all countries on the basis of its objective national interest – safeguarding the sovereignty, territorial integrity, economic wellbeing and the national security of Sri Lanka. Conscious of the externally influences, serious security challenges Sri Lanka has faced: for over 30 years due to separatist terrorism (Gupta, 1984; Aryasinha, 2001); and subsequently having being vulnerable to Islamic terrorism/radicalization (Barton, 2019), on security Sri Lanka cannot afford to drop its guard and be over-dependent on any single outside power. As with the need to retain sufficient vigil on the ground, this is particularly true in the realm of ocean security and also air security, where impermeability will be vital to Sri Lanka’s strength as both a state and an economy.

With respect to requests for access to Sri Lankan ports, airports, and to its waters for research purposes, which is emerging as the main irritant in the relations with India, China and the US, each such request must be carefully reviewed based on real-time data and permission granted based on a Standard Operational Procedure (SOP) on a defence services port/airport call policy. Foreign Minister Ali Sabry while noting that such a policy was recently finalized and sent to all countries that deployed their vessels to Sri Lankan waters during the last ten years, has stated that the government has announced what has been described as “a twelve-month moratorium on research vessels from any country starting from January, next year (2024)” (Bandara, 2023). The Foreign Minister has added that “This is for us to do some capacity development so that we can participate in such research activities as equal partners”. Previously, visits by Chinese research vessels Yuan Wang 5 to the Hambantota Port in August 2022 and Shi Yan 6 to the Colombo Port for survey purposes in October 2023 was to raise concerns mainly from India, but also the US (Alam, 2023), and a request for a third Chinese research vessel Xiang Yang Hong 3 seeking to arrive in January 2024 was pending at the time. Earlier, a senior Minister was quoted as saying “The arrival of these ships creates serious diplomatic tensions, and it (2024) is an election year. Such ship visits can be highly disruptive for the region and Sri Lanka, because of the pressure the Government may come under” (Fernando, 2023).

It is noted that, although media coverage has tended to focus on Chinese research vessels, Sri Lanka has over the years received research vessels from a number of other countries as well, while naval vessels from all countries frequently use Sri Lanka as a port of call, which besides earning goodwill, is also an important foreign exchange earner. However, in order to maintain equity, Sri Lanka must ensure that no separate long-term agreements are entered into in future with any country concerning Sri Lankan airports, ports, land or sea use, for defence related purposes. Also, conscious of the rapid advances in military technology and particularly the increasing propensity for dual-use technology, Sri Lankan authorities must develop the technical expertise to conclusively make assessments and determinations as to the veracity of any concerns raised speedily, so that in future this aspect is kept under objective scrutiny and does not lead to propaganda and tarnish Sri Lanka’s image.

Securing the foundation of a sustainable foreign policy for Sri Lanka also requires an unwavering dedication to upholding a ‘rules-based order’ within the expansive maritime domain surrounding Sri Lanka. Crucial to this endeavor is the imperative that Sri Lanka rigorously embraces principles of fairness, aiming to ensure equitable treatment for all stakeholders involved in the intricate web of maritime affairs. This commitment should be deeply rooted in the strict compliance with established international legal frameworks, with a specific emphasis on adherence to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). By steadfastly adhering to such international norms, Sri Lanka not only reinforces its diplomatic credibility, but also actively contributes to the cultivation of cooperative relations and regional stability.

Additionally, to off-set the uninvited attention the country has received in recent times in the politico-strategic realm in the IOR, Sri Lanka must also seek to pro-actively play a more functional role in non-traditional security sphere in the Indian Ocean – drawing attention to the importance of issues such as the freedom of navigation and the safety and security of the Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs) in the Indian Ocean. These initiatives mooted during Sri Lanka’s October 2018 initiative of the Track 1.5 Conference ‘The Indian Ocean: Defining our Future’ hosted in Colombo, was possibly the last occasion that saw the engagement by all of the maritime states and users of the Indian Ocean in a single forum in recent times. As the new Chair of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) since October 2023, Sri Lanka has vowed to bring the focus back to the ‘Indian Ocean Region’, as evident in the theme for Sri Lanka’s chairmanship “Strengthening regional architecture: Reinforcing Indian Ocean identity”. In this regard, Sri Lanka can also build on the useful role it played as Chair of the IORA Working Group on Maritime Safety and Security (2018-2023), which could have a spillover effect on trade, investment, and regional security – both multilaterally, but also in enhancing Sri Lanka’s bilateral relations with states in the Southeast Asian and African regions.

Conscious that geo-politics is deeply intertwined with geo-economics, it is also important that Sri Lanka diversify the present economic/market dependence for exports & imports, investment, tourists, and migrant employment opportunities, in order for Sri Lanka to develop a more balanced relationship with the major powers with interests in the Indian Ocean Region. This would allow Sri Lanka to guard against disruptions that could be caused by external policy changes directed at Sri Lanka – as retaliation for any displeasure arising out of resisting possible pressures imposed, or in the event that Sri Lanka is to become collateral in broader global actions by the major powers. In this respect, ensuring that the Colombo International Financial City (CIFC) remains a level playing field which can draw investment from all countries will be pivotal to conveying Sri Lanka’s strength as a credible investment destination, in order that Sri Lanka could draw western investment as initially anticipated.

Beyond its legitimate justification, human rights issues concerning Sri Lanka are also increasingly being used as leverage – in both bringing pressure on Sri Lanka and also in defending Sri Lanka, to further the strategic interests in the region by individual and groups of countries. In facing the challenges posed to Sri Lanka in multilateral fora with regard to human rights issues, it is important that Sri Lanka regains the support of the Global South, including that of India, and greater understanding from all countries including Sri Lanka’s detractors.

Besides the major power rivalry in the IOR; there are also several important additional global dynamics that policymakers must both contend with, and where possible seek to take advantage of, as they grapple with crafting a sustainable foreign policy these include the broader volatile global power politics, geo-economics, and climate change; the crisis in multilateralism; the emerging coalitions in the UN voting patterns; the quest by the Global South to reclaim the middle ground, and the evolving role of non-state actors, including diaspora (Aryasinha, 2023b).

- Conclusions

It is within the totality of these circumstances that Sri Lanka’s quest to navigate in an increasingly ‘zero-sum’ environment in the IOR must be understood. Operationalizing most of the above-mentioned elements would require that Sri Lanka develops a clear ‘domestic consensus’ on its own perspectives and interests, and engages in careful negotiations with relevant interlocutors. In parallel, it is important for Sri Lanka to initiate action unilaterally in the following three areas.

First, despite diplomatic practice being clear that the soil of one state must not be used to launch propaganda attacks on third countries, as the foothold of major powers has increased within Sri Lanka particularly over the past decade, through their diplomatic missions based in Sri Lanka regularly and during visits of dignitaries to Sri Lanka occasionally, these powers have shown a tendency to criticize the policies and practices of third countries operating within Sri Lanka. This has complicated Sri Lanka’s exercise of an independent foreign policy and must be checked, as without due diligence, Sri Lanka faces the potential risk of being caught in the diplomatic crossfire.

Second, Sri Lanka must also be conscious of the public sensitivities generated by the competing major power influences/interference in Sri Lanka, on which up to now there has been little objective research or analysis. These issues must be managed by Sri Lanka with mindfulness, as if done otherwise, Sri Lanka will run the risk of a single State, or a combination of States parties who feel excluded, together with their disgruntled/motivated allies both within and outside the country, resorting to visible retaliation or worse to surreptitious de-stabilization of Sri Lanka to serve their respective interests. Sri Lanka must remain extremely vigilant about this possibility.

Third, the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the raging situation in the Middle East, and the regular sabre-rattling involving the ostentatious display of military power in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Straits, are reminders that peace in the region cannot be taken for granted. Hence, Sri Lanka foreign policy needs to anticipate scenarios and vulnerabilities that it could be presented with in future, which could be based on a major power clash in the Indian Ocean over which Sri Lanka would have little control, and hence also develop policy options and leavers to deal with such an eventuality.

While it is obvious that Sri Lanka is unlikely to be able to change the circumstances that prompt India, China and the US to behave in a particular manner, and taking sides is untenable as it would result in Sri Lanka being taken for granted in a ‘winner takes it all’ setting and Sri Lanka losing leverage, it is imperative that Sri Lanka scope out options that might be available to the country in navigating these challenges.

While necessarily non-exhaustive, and also country specific, nevertheless any lessons that can be drawn from Sri Lanka’s experience in dealing with these issues, could be also useful to other SSAs and comparable developing countries that might be facing a similar predicament.

*Ambassador Ravinatha Aryasinha is the Executive Director of the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). A retired member of the Sri Lanka Foreign Service (SLFS), he was the Foreign Secretary of Sri Lanka 2018 – 2020, and also served as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador to the USA; to Belgium, Luxembourg and to the European Union; and as Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva. He holds a BA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, University of Peradeniya and a MA in International Relations, University of Colombo. He was also a ‘Hurst Fellow’ in International Relations at the School of International Service (SIS), American University, Washington DC, USA.

References

Alam, M. (2023, September 28). Why is India & US Concerned Over Chinese Research Ship’s Visit to Sri Lanka. News 18

https://www.news18.com/explainers/china-research-ship-shi-yan-6-sri-lanka-ports colombo-hambantota-8595198.html

Aryasinha, R. (2001). Terrorism, the LTTE and the conflict in Sri Lanka. Conflict, Security & Development, 1(02), 25-50.

Aryasinha, R. (2023a) Approximating ‘Sri Lanka’s National Interest’, a ‘Sri Lankan Worldview’ and ‘Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy Posture’. INCOIRe-2023: Geopolitics of Regionalism, IR Department Annual Conference, University of Colombo, 9-10 Sept 2023.

Aryasinha, R. (2023b). A ‘Global Order’ in Flux: Challenges and Opportunities. LKI Website. September 19, 2023. Retrieved from: https://lki.lk/publication/a-global-order-in-flux-challenges-and-opportunities/

Aryasinha, R. (2023c). Straddling the major power competition in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR): The scope and limits of Sri Lanka’s ‘neutrality’ in a Zero-sum Environment, International Conference on ‘Ocean Security: South Asia and the Indian Ocean’. Regional Centre for Strategic Studies (RCSS), Colombo, 16 October 2023.

Bandara, K. (2023, December 19). Geopolitical chess game: Sri Lanka declares pause on foreign research vessels for one year. Daily Mirror. https://www.dailymirror.lk/front-page/Geopolitical-chess-game-Sri-Lanka-declares-pause-on-foreign-research-vessels-for-one-year/238-273527

Banerjee, A. (2023, March 29). Bhutan changes stance, says China party to Doklam dispute. The Tribune.

https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/bhutan-changes-stance-says-china-party-to-doklam-dispute-492077

Barton, G. (2019, April 25). Islamic State has claimed responsibility for the Sri Lanka terror attack. Here’s what that means. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/islamic-state-has-claimed-responsibility-for-the-sri-lanka-terror-attack-heres-what-that-means-115915

Chaudhury, D.R. (2023, October 24). China may leverage Sri Lanka loan rejig to get maximum concessions. Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/china-may- leverage-sri-lanka-loan-rejig-to-get-maximum-concessions/articleshow/104660174.cms

Coomaraswamy, I. (2017). Quoted in ‘China-backed port sparks Sri Lanka sovereignty fears -Deal to cede control of trade hub prompts Indian moves to match Beijing’s clout’. Simon Mundy in Hambantota, Sri Lanka, Financial Times (UK), 24 October 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/f8262d56-a6a0-11e7-ab55-27219df83c97

Daily Mirror. (2023, December 14). IMF wants SL to finalize deals with creditors ahead second review in June.

https://www.msn.com/en-xl/news/other/imf-wants-sl-to-finalize-deals-with-creditors-ahead- second-review-in-june/ar-AA1lrvNc

Fernando, A. (2023, December 17). Foreign research vessels: Govt. moots moratorium. The Morning. https://www.themorning.lk/articles/Fv6pu0JsCIaXtS3B5mBq

Fernando, S. (2023, December 3). The Thucydides Trap and Bilateral Relations. The Island. https://island.lk/the-thucydides-trap-and-bilateral-relations/

Financial Times. (2023). IMF Executive Board gives thumbs up in first review; releases $ 337 m second tranche. 13 December 2023. https://www.ft.lk/frontpage/IMF-Executive-Board-gives-thumbs-up-in-first-review-releases-337-m-second-tranche/44-756261

First Post. (2023, July 21). Will China Derail India-Sri Lanka Relations? Vantage with Palki Sharma. [Video]. YouTube.

Gunarathne, P. N. M. (2021). Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy from 1994 to 2019: Non-alignment and Sino-Lanka relations. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Gunasekera, S.N (2015). Bandwagoning, Balancing, and Small States: A Case of Sri Lanka. Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 28; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025. Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education, https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/809adc2e96225c66bb402ada0923652b8d2f7a4d

Gupta, S. (1984, March 31). Large number of Sri Lankan Tamil rebels acquires training in obscure parts of Tamil

Nadu. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/investigation/story/19840331-large-number-of-sri-lankan-tamil-rebels-acquires-training-in-obscure-parts-of-tamil-nadu-802910-1984-03-31

Hasan, M. (2023, June 28). How India, the US, and China Can Impact Bangladesh’s Impending Election. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2023/06/how-india-the-us-and-china-can-impact-bangladeshs-impending-election/

Hewage, K. (2017, October 5). China in South Asia: Sri Lanka’s “Strategic Promiscuity”. South Asian Voices. https://southasianvoices.org/china-in-south-asia-sri-lankas-strategic-promiscuity/

Hewage, K. (2023, July 25) China in South Asia: Sri Lanka’s Elusive Attempts to Balance Between India and China. South Asian Voices. https://southasianvoices.org/china-in-south-asia-sri-lankas-elusive-attempts to-balance-between-india-and-china/

Indian Express. (2023, October 1). Chinese research ship to visit Sri Lanka, US raises concerns: What has happened, and why? https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/everyday-explainers/sri-lanka-chinese-research-ship-explained-8957466/

International Committee of the Red Cross. (2002) Law of Armed Conflict: Neutrality. June, 2002. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/law8_final.pdf

Jayasekera, S. (2022). Defence and Strategic Studies. https://irc.kdu.ac.lk/2022/Plenary-Session-2-Defence-and-Strategic-Studies.php

Kandaudahewa, H. (2023) Sri Lanka’s Strategic Dilemma: Navigating Great-Power Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific. Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, pp 121- 126.

Ladduwahetty, N. (2023, August 22) Neutral foreign policy in practice. The Island. https://island.lk/neutral-foreign-policy-in-practice/

Laskar, R.H. (2023, August 12). ‘Monitoring all developments’: India on Chinese naval vessel’s visit to Colombo. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-carefully-monitors-chinese-naval-vessel-s-visit-to-sri-lanka-amid-security-concerns-101691770745908.html

Lottaz, P. andJayathilake, A.P. (2021, March 19). Sri Lanka Discovers Neutrality: Strategy or Excuse? There are sound domestic and strategic reasons for Colombo to pursue a strategy of neutrality. The Diplomat.

https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/sri-lanka-discovers-neutrality-strategy-or-excuse/

Macan-Markar, M. (2023, October 1). Maldives’ Muizzu marches to victory on anti-India drumbeat. Nikkei Asia.

https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Maldives-Muizzu-marches-to-victory-on-anti-India-drumbeat

Manatunga, R., (2023). How has power competition in the Indian Ocean Region impacted the foreign policy strategies of Small South Asian States: Case study of Bangladesh. Unpublished MAS Research Paper, 24 April 2023, Geneva Centre for Security Policy, Switzerland.

Martyn, K. (2023). The New Wave: Resetting, Restraint and Re-engagement of US-Sri Lanka Relations. Presentation made at Expert Roundtable Consultation on “Strengthening Engagement in U.S-Sri Lanka Relations”, 18 October 2023, Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute, Colombo. https://lki.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/LKI-Takeaways-US-SL-Roundtable-Consultation.pdf

Merriam Webster (n.d) Merriam Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/zero-sum

Menon, S (2016). Choices: Inside the making of India’s foreign policy. Brookings Institution Press.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh. (2023). Indo-Pacific Outlook of Bangladesh.

https://mofa.gov.bd/site/press_release/d8d7189a-7695-4ff5-9e2b-903fe0070ec9

Mudugamuwa, I. (2023, September 8) Sound foreign policy helped fast track debt restructuring – Minister. Daily News. https://www.dailynews.lk/2023/12/08/local/280735/sound-foreign-policy-helped-fast-track-debt restructuring-minister/

Palihakkara, H.M.G.S. (2023, February 5). Diplomacy challenges: Taxing but doable. Sunday Times

https://www.sundaytimes.lk/230205/sunday-times-2/diplomacy-challenges-taxing-but-doable-510633.html

Palihakkara, H.M.G.S. (2023, August 17). Challenge for Sri Lanka demonstrates it is after economic benefits and not geopolitical mischief. The Island. https://island.lk/challenge-for-sri-lanka-demonstrates-it-is-after-economic-benefits-and-not-geopolitical-mischief/

PMD (2023a) ‘Ocean Nations: The third Annual Indo-Pacific Islands Dialogue,’ moderated by Dan Baer, Senior Vice President for Policy Research at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and hosted by the Carnegie Endowment and Sasakawa Foundation. 18 October 2023.

https://www.presidentsoffice.gov.lk/index.php/2023/09/19/island-nations-of-the-indian-ocean-and-south-pacific-urge-non-interference-in-great-power-rivalry/

PMD (2023b). President Wickremesinghe Envisions Indian Ocean’s Crucial Role in Emerging New World Order at Galle Dialogue. https://pmd.gov.lk/news/president-wickremesinghe-envisions-indian-oceans-crucial-role-in-emerging-new-world-order-at-galle-dialogue/

Pradhan, T.R. (2022, February 27). Parliament ratifies MCC compact after years of delay. Kathmandu Post.

https://kathmandupost.com/national/2022/02/27/nepal-parliament-ratifies-mcc-compact

Reuters. (2021). Bangladesh: Chinese Envoy’s Warning Against Joining Quad ‘Very Unfortunate’. 5 November 2021. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/warning-05112021182619.html

Samaranayake, N. (2023a). Smaller South Asian Countries and the US Indo-Pacific Strategy at One Year.

Asia-Pacific Bulletin, 642. May 21.

https://www.eastwestcenter.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/Smaller%20South%20Asian%20Countries%20and%20the%20US%20Indo-

Pacific%20Strategy%20at%20One%20Year.pdf

Samaranayake, N. (2023b). Sri Lanka navigating major power rivalry: How domestic drivers collide with the international system. Small States & Territories, 6(1), 49-68. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/109184/1/SST6(1)A4.pdf

Senaratne, W. B. (2022). US Relations with Sri Lanka: a case of Impulsiveness, Missed Opportunities and Strategic Competition. In O. Turner, N. Nymalm, W. Aslam (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of US Foreign Policy in the Indo-Pacific. Routledge.

Senaratne, W.B. (2023b). Sri Lanka’s Tightrope: Non-alignment, Economics, and Diplomacy in the US- China Struggle. In A. Shivamurthy (Ed.). US-China Competition: Perspectives from the Neighbourhood. ORF Special Report No. 218.

https://www.academia.edu/112526456/Sri_Lankas_Tightrope_Non_alignment_Economics_and_Diplomacy_in_the_US_China_Struggle?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper

Shain, Y., & Aryasinha, R. (2006). Spoilers or catalysts: The role of diaspora in peace processes. In E.Newman & O. Richmond (Eds.), Challenges to Peace Building: Managing Spoilers during conflict resolution. U.N. University Press.

Smith, J. (2019). Sri Lanka: a test case for the free and open Indo-Pacific strategy. Heritage Foundation.

https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/sri-lanka-test-case-the-free-and-open-indo-pacific-strategy

Tharoor, I. (2022, July 20). China has a hand in Sri Lanka’s economic calamity. Washington Post.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/07/20/sri-lanka-china-debt-trap/

The Straits Times (2020) US Secretary of State Pompeo slams ‘predator’ China on Sri Lanka trip, Associated

Press. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/us-secretary-of-state-pompeo-slams-predator-china-on-sri-lanka-trip

US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. (2009). Sri Lanka: Recharting US Strategy After the War. 111th Cong., 1st sess. 7 December 2009.

https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SRI.pdf

Weerakoon, D. (2023). https://lki.lk/events/lki-foreign-policy-forum-changing-global-dynamics-implications-for-sri-lanka/ (00.56-01.10 Hrs)

Wignaraja. G. (2022). Reflecting on US-China rivalries in post-conflict Sri Lanka. In F. Heiduk (Ed.) Asian Geopolitics and the US–China Rivalry. Routledge.

Wooley, A. and Zhang, S. (2023, July 27) Beijing is going places – and building naval bases, here are the top

destinations that might be next. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/27/china-military-naval-bases-plan-infrastructure/