A Comprehensive Examination of Environmental, Economic, Social, and Legal Implications

Synopsis:

The Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project (SSCP), aimed at creating a direct shipping route between India’s east and west coasts, poses serious environmental, economic, social, and legal risks. The project threatens the ecologically sensitive Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait, home to endangered species and vital marine resources. Economically, the canal offers minimal benefits while incurring high maintenance costs, and it risks displacing local fishing communities. Culturally, it threatens the sacred “Rama Sethu” site, sparking religious opposition. The project also raises international concerns, especially with Sri Lanka, over potential environmental damage.

The proposed Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project (SSCP), which seeks to carve a navigational route through the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait, aims to connect India’s east and west coasts.

While touted as an economic boon that would reduce travel time for ships, the project raises profound environmental, economic, social, and legal concerns that could have devastating and irreversible consequences for the region. Given its scope and potential impact, this project warrants critical scrutiny and reconsideration, particularly in light of its ecological, cultural, and geopolitical ramifications.

The Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait are among the most ecologically sensitive areas in the world, home to over 3,600 species of plants and animals. These include endangered species like sea turtles, whales, dolphins, and the dugong (sea cow), all of which play crucial roles in maintaining the region’s delicate ecosystems. The construction of an 83 km deep-water channel through this biologically rich marine area would pose a significant threat to this unique biodiversity.

Dredging the sea bed to create the channel could stir up sediments and potentially release harmful toxins that have been trapped in the sea floor for years, thus adversely affecting marine life. The proposed dredging could also lead to the destruction of coral reefs, which are already suffering from the effects of ocean acidification. Moreover, alterations in water temperature, salinity, and nutrient flows could destabilize the entire ecosystem, leading to coastal erosion and a potential collapse of vital marine habitats. Such disruption could result in the loss of numerous species that depend on these ecosystems for survival.

The Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait also support important marine resources, such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and seagrasses, which are vital for both the marine ecosystem and local livelihoods. The region’s mangrove forests and seagrass beds serve as important breeding and feeding grounds for a variety of marine species, including juvenile fish. For many local fishing communities, these resources are not only part of the region’s biodiversity but also essential to their way of life. The potential disruption of these ecosystems due to the canal’s construction would threaten the region’s biological wealth and the sustainability of local economies that depend on these natural resources.

The economic arguments supporting the SSCP fall short when closely examined. While proponents suggest that the canal would save significant time for ships by offering a shortcut between India’s east and west coasts, shipping experts argue that the benefits are minimal. The narrow, shallow nature of the proposed waterway would require ships to slow down drastically, negating any time savings. Furthermore, the canal would require continuous dredging to keep it navigable, imposing substantial ongoing costs that would likely outweigh the marginal economic benefits.

A study by the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) in 1988 highlighted the technical challenges and environmental risks associated with the project. Dredging and maintaining the canal would be a financial burden on the Indian government, with no guarantee of positive returns. Moreover, local fishing communities that rely on the region’s marine resources for their livelihood would be disproportionately affected. The displacement of these communities and the degradation of local ecosystems could result in severe socio-economic consequences, exacerbating existing regional inequalities.

The SSCP poses significant social and cultural challenges, particularly for local communities. The canal’s proposed route would disrupt the “Rama Sethu,” a structure of limestone shoals that holds immense cultural and religious significance for Hindus. Believed to be the remnants of the bridge constructed by Lord Rama in the epic Ramayana, the Rama Sethu is a sacred site for millions of Hindus. The potential destruction of this landmark has sparked widespread opposition from religious groups, including petitions to halt the project on religious grounds.

Beyond the cultural implications, the project threatens the livelihoods and traditional ways of life of local fishing communities. Displacement and the disruption of fishing resources would affect these communities’ ability to sustain themselves, pushing them further into poverty and social instability. As noted by S.C. Withana and C.V. Liyanawatte of the Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, the construction of the SSCP would create significant social upheaval in a region already grappling with socio-economic challenges.

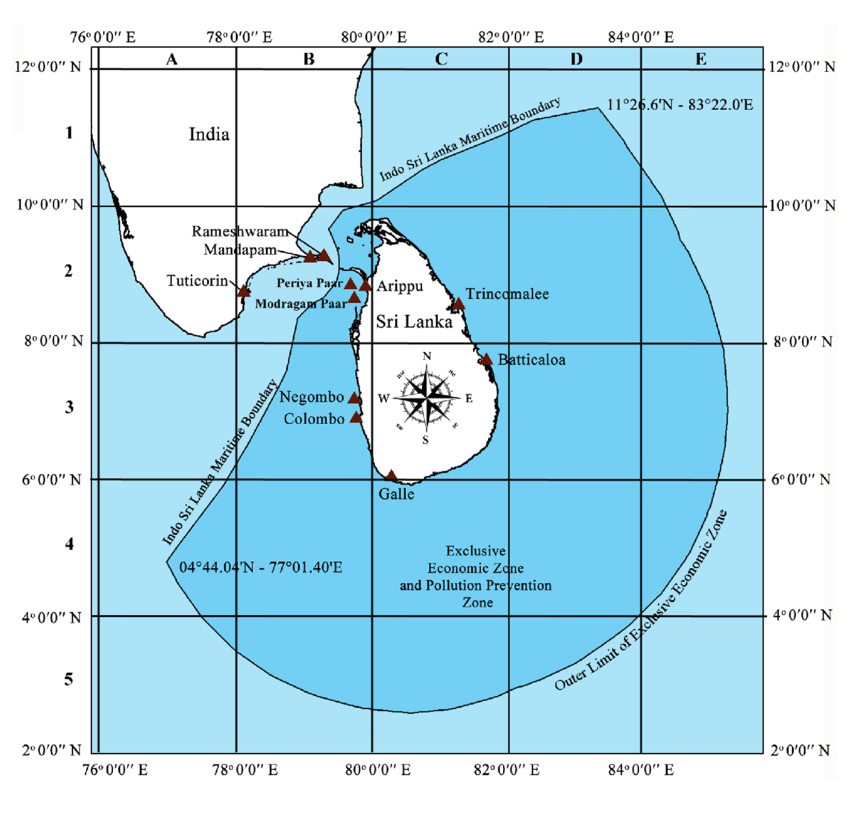

The SSCP has wider geopolitical implications, particularly for India’s relationship with Sri Lanka. While the canal is proposed to be built within India’s territorial waters, Sri Lanka has raised serious concerns about its environmental impact. Given the proximity of the canal to Sri Lanka’s coast, the project’s environmental consequences do not respect national borders. In 2005, Sri Lanka called for the establishment of a joint Indo-Sri Lankan mechanism to monitor the project’s impact, but these concerns have largely been ignored by the Indian authorities.

Sri Lankan experts, such as Withana and Liyanawatte, have criticized the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) conducted by India for neglecting to incorporate the latest scientific studies on sediment dynamics and marine resource depletion in the Palk Bay. The absence of a collaborative, cross-border environmental and social impact assessment undermines the principles of international cooperation outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which mandates that states should ensure their activities do not cause harm to neighboring countries’ marine environments.

The project’s impact extends far beyond the immediate vicinity of the canal, especially with regard to the high tide line, which could have significant consequences for both Sri Lanka and India.

Rising sea levels, coupled with changes in salinity and the release of toxins from disturbed sediments, can drastically affect rivers in both nations. Sri Lanka has an estimated 103 rivers, and these river systems, such as the Mahaweli, Kelani, and Walawe Rivers, could experience a rise in salinity, leading to disruptions in freshwater availability and negatively impacting agriculture, fisheries, and local populations. In India, rivers like the Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery may also face the threat of saline intrusion, compromising their ecological balance and sustainability for agriculture.

Moreover, the canal’s construction could damage nearby rivers, bays, and coastal areas by altering sediment flows and water currents. The total length of Sri Lanka’s coastline is 1,340 km, and its territorial waters extend up to 22 km from that shore to cover a total area of about 21,500 km². The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends outward 370 km from the shore, covering an area of about 510,000 km² of the Indian Ocean. These delicate coastal ecosystems could be severely impacted by the changes in water flow and sediment deposition caused by the canal’s construction. The disruption of sediment transport could damage bays, beaches, and the coastal environment, leading to long-term ecological degradation.

Additionally, increased salinity and the release of toxic sediments could cause significant social and economic changes. The livelihoods of thousands of people in coastal regions, particularly those dependent on fishing and agriculture, would be endangered. Communities along these rivers may suffer from a lack of freshwater resources, resulting in intensified poverty, displacement, and migration. The social unrest caused by these changes could destabilize local economies, leading to long-term socio-economic upheaval.

The canal’s underwater current system could have unpredictable consequences on the global marine environment. Alterations in sea flow patterns could affect marine currents that regulate weather systems, fish migration, and global climate. Such shifts could disrupt marine ecosystems around the world, impacting fishing industries and biodiversity in far-flung areas. The full scope of the canal’s impact on the world’s oceans cannot be overstated, and its potential for cascading negative effects across multiple ecosystems is profound.

Sri Lanka could invoke UNCLOS to seek redress for the environmental degradation caused by the canal. As per Article 194(2) of UNCLOS, India is obligated to take measures that do not result in pollution or damage to Sri Lanka’s marine environment. Failure to address these concerns could lead to legal disputes, as seen in the 2003 case between Malaysia and Singapore over land reclamation. Sri Lanka could, if necessary, take the matter to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) for binding decisions.

The Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project is fraught with significant environmental, economic, social, and legal challenges that cannot be overlooked. The project poses an existential threat to one of the world’s most biodiverse marine ecosystems, risks exacerbating socio-economic inequalities, and threatens to destabilize India’s geopolitical relations with Sri Lanka. The financial cost of the project, coupled with the marginal benefits it would provide, makes it an unwise and unsustainable investment.

In light of these considerations, the implementation of the SSCP should be reconsidered. Authorities must explore alternative solutions that prioritize the preservation of the region’s natural resources, the protection of local communities, and the safeguarding of international relations. The future of the Gulf of Mannar, the Palk Strait, and the surrounding regions depends on a balanced approach that recognizes the interconnectedness of environmental, economic, social, and geopolitical factors. Only by fostering dialogue, collaboration, and long-term sustainability can India and Sri Lanka ensure that their shared natural heritage is protected for future generations.

As a deep-sea diver and beach field supervisor with over 25 years of experience in beach and marine environments, I have spent countless hours underwater, observing the beauty and fragility of marine ecosystems. During this time, I’ve witnessed firsthand the environmental damage caused by human activities such as dredging and construction projects. I’ve seen coral reefs, once teeming with life, now reduced to barren, bleached structures. I’ve encountered seagrass beds destroyed by dredging, leaving behind lifeless patches of sand where marine species once thrived.

These personal experiences have shaped my understanding of the delicate balance that exists beneath the surface and the profound impact such projects can have on our oceans. The potential damage from the Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project is a matter of great concern. The dredging and disruption of these ecosystems could have far-reaching consequences, not only for marine life but also for the livelihoods of local communities who rely on these resources. My firsthand knowledge compels me to speak out and oppose this project before irreversible damage occurs.

“The British envisioned a navigational canal through the Gulf of Mannar to strengthen their control over Indian waters, enhance trade efficiency, and secure their maritime dominance in the region.”

By Palitha Ariyarathna

Former Beachfield and Life Safety Officer and Deep Sea Diver

Note:

Geopolitical – This Article is Based on Research Writing

References:

· S.C. Withana & C.V. Liyanawatte (2005) – Highlight environmental and social concerns of SSCP, focusing on sediment dynamics and marine biodiversity.

· NEERI Report (1988) – Discusses technical challenges and environmental risks of SSCP, especially from dredging and canal maintenance.

· UNCLOS Article 194(2) – Emphasizes states’ obligations to prevent transboundary pollution, relevant to Sri Lanka’s concerns over SSCP.

· Sri Lanka Ministry of Environment (2005) – Addresses risks to coastal waters, including coral reefs and marine habitats.

· Sri Lanka Coast Conservation Department (2011) – Highlights risks to Sri Lanka’s coastline and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) from the SSCP.

· Sri Lanka Geological Survey & Mines Bureau – Provides insights into sediment transport and coastal dynamics in the Gulf of Mannar.

· WWF India (2005) – Discusses environmental impacts on the Gulf of Mannar, highlighting risks to endangered species.

· NIO Report (2010) – Assesses the effects of dredging on salinity and marine ecosystems in the Palk Strait.

· ITLOS – Legal perspectives on cross-border environmental disputes under UNCLOS.

· Sri Lanka Department of Fisheries (2010) – Discusses potential damage to fisheries from SSCP-related changes in marine environments.

· EFL Sri Lanka (2010) – Assesses the irreversible ecological damage to the Gulf of Mannar from large infrastructure projects.